In one of the subjects that I tutor, I teach students about the social determinants of health. One [social determinant] is high levels of job related stress and the impacts on physical and mental health. I don’t tell them that as a casual academic that is exactly what you get. Precarious employment status means – you have to self-organise: find new contracts and chase work (very humiliating), underemployment (periods of time where there are not any opportunities for any kinds of teaching work (the reason I hate Christmas), little job control (you have to take orders from above – if you do not you will not work there again), little hope of transitioning into stable employment (full-time jobs – as if), no sick leave (teaching 2 days after you have a radical nephrectomy – just try not to bleed in class), no reward for long service (you’ve been tutoring for how long?) and the run off effects of… housing precarity (no income to pay the rent – I have to do deliveroo when desparate), high anxiety levels (impacts on productivity), low levels of self-esteem (I must be doing something wrong), no stable place to work (forced to hot desk), no recognition (invisible in the workplace), having to negotiate IT, email, timesheets for each employer (try having different platforms where one works on internet explorer, one on chrome, one on mozilla…etc etc) which all lead to: real doubt about promoting the benefits of graduate study to students when the university system transitions to a corporate model that aims to maximize profits rather than value employees and foster intellectual thought.

I was on three different casual contracts with the same university. Two of the contracts were research assistant roles and the other was four hours a week of teaching. I arrived on campus one morning at 8.45 and went to grab some teaching materials out of my office to take to my 9am tutorial. I swiped my pass to enter the building, but the door wouldn’t open. The pass reader said ‘invalid’. I tried a few times, but no luck. I started to panic a bit – 9am was getting closer. Then I remembered – one of my research contracts had expired the previous day. In the system, my building access must have been linked to that contract. I’d been working at the university for nearly three years, I was two weeks into the semester-long course I was teaching, plus I had another research contract for the next six months, but the system had decided I don’t work there anymore because another contract had expired at midnight the night before. I raced across campus to the security office and told a security guard that my pass wouldn’t work. He said, “Did one of your contracts expire?” Apparently, it happened often. I got to my class ten minutes late, covered in sweat, and tried to pull myself together long enough to run a good two-hour tutorial. Fortunately, the students in that class were great. They were engaged and fun to work with. But the whole time, I was feeling like a cog in a system that had no interest in me. Far from a valued member of staff, I was barely a person. All I was to the university was a collection of hours on a spreadsheet. The hours on a contract were all used up and so I was now invalid. That same semester, I taught another class on a different campus. My commute to get that campus was two hours and there was no other work I could do there. So it was a four hour round commute for two hours of paid work, once a week for a whole semester. I could have said no to taking that class. I could have survived without that two hours pay. But what if I said no and then the person coordinating the class didn’t offer me any work the next semester? The solution to all of this is easy. If you need people to teach classes and do research, then offer them on-going jobs. But we’re not people. We’re just collections of hours on a spreadsheet somewhere.

I feel like a failure. I don’t have the drive to compete with friends and peers; I don’t have the emotional energy required to work late into the night and on the weekends for free; I don’t want to play a toxic game. I feel like I put my life on hold during the PhD. I cannot do that anymore. I will not go back to that unhealthy life destroying void. But that makes me a failure in this place.

I had the experience of walking away from a continuing position, not once but twice, due to family reasons; I had to relocate to different cities due to my partner’s employment and parents’ deteriorating health. I was in various short-term contracts for a period of nine years before gaining access to a continuing position. This experience of precarious employment made it difficult to plan and invest in my research and associated collaborative relations, and ruled me out from accessing research funds. I feel that this has cost me dearly, leading to a slow progression in my career compared with my peers. The experience of short-term contracts also created a financial burden for us as a family, as we had considerable uncertainty, making it difficult to decide where to live and also to access a mortgage to purchase a home. The short-term contracts, and the uncertainty and financial stress this situation created, were a source of considerable personal stress, putting pressure on my relationship and leading to a period of severe insomnia and weight-gain. Now after being in a continuing position for a number of years, I still feel I have not quite recovered from the disruption associated with changing institutions and the period of short-term contracts. I sometimes feel that those who have had a more straightforward and stable trajectory in their careers do not appreciate the personal and professional toll disruptions and precarious employment situations have on their colleagues.

I fixed it!

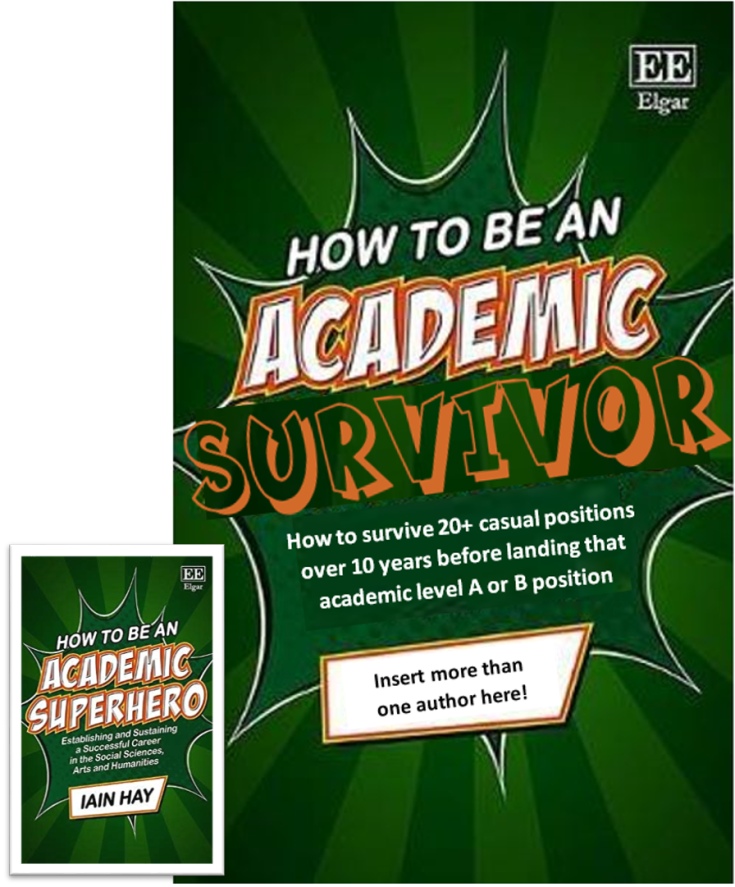

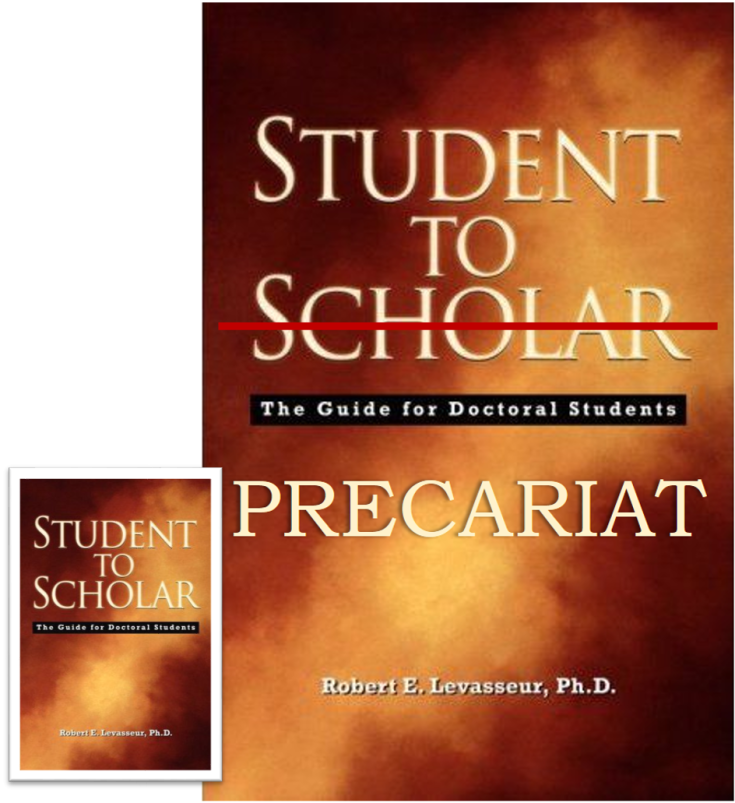

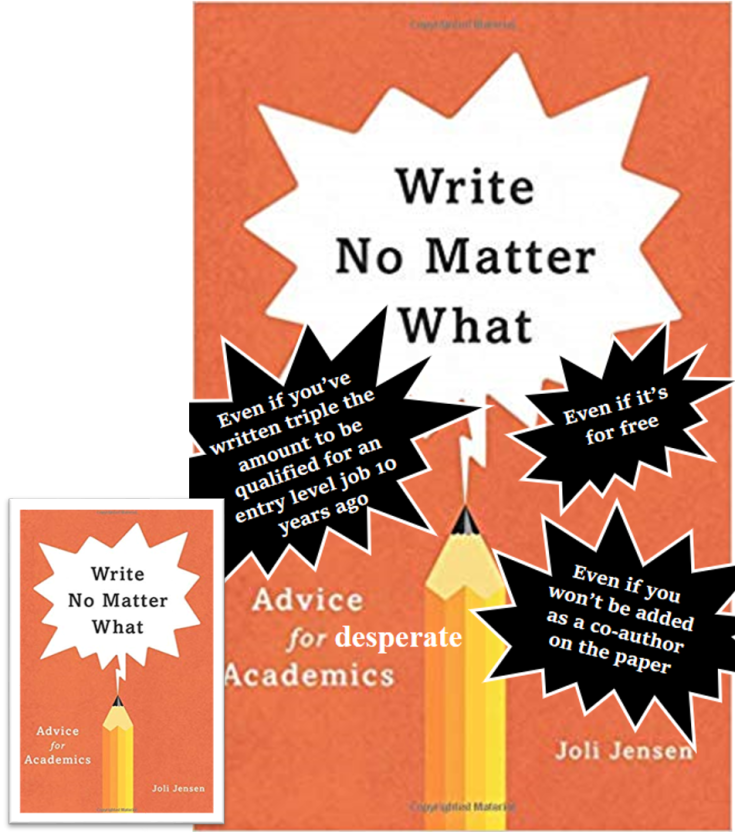

I was having one of those ‘why am I still in academia?’ mornings, so I decided to waste it away by ‘fixing’ all the academic book titles that annoy me. I hope it provokes a cheeky smile for some of you!

I had stereotypes about academia and I knew I will never work in academia. After a year I started working in academia and after completing my PhD I joined academia almost full-time. I realised it is not as crazy and sterile as I imagined.

I’ve been precariously employed in academia for enough time that it has rewired my brain – at least the areas to do with scholarship. I now have the attention span of a gnat, the ability to dive as deep into a particular subject area as I do into a puddle, and my ‘research’, when I get a chance to do it, is also superficial and shallow only as I have only time and energy to skim the surface of anything: read an abstract, the first page and the conclusion of any paper, scan the subheadings of a research report, press Cntl+F on a PDF looking for particular keywords that I can stick into my latest briefing paper. On the plus side, my speed reading has tremendously improved as has my “That’ll have to do” approach to academic work.

| My career has continually been on an upward trajectory, despite having been only offered six-month to one-year contracts (though by the same research centre) for nearly 10 years now. I have successfully won and led projects and contribute to others’. This is a testament to everyone in my centre and our ability and doggedness in constantly applying for grants. As an applied discipline, there is significant impact in terms of policy influence as well as having high social engagement, having been invited to contribute to media (in print, radio & television), government inquiries and hearings, and present at public forums. The precarity of surviving on grant money alone, however, can be quite stressful, not just to those who rely on that income to support their salaries, but also to the directors and managers who want to keep everyone employed, especially those who show promise. This in some ways bring the centre staff closer together, partly because most of us are in the same boat but also that we work well together; on the flip side there is a significant lack of understanding from the rest of the faculty who only see that we have this constant stream of grant success and that we’re ‘lucky’ that we get to work on research all the time while complaining that their disciplines (which are not that dissimilar to ours) don’t ever get funding support so they don’t get to work on research. There is a severe case of misunderstanding of what research-only staff do, especially in this era where many universities are highly focused on lifting their international rankings, rankings that are solely contributed by research functions, which in turn bring in domestic and international students. |

Because precarity surrounds me, but i am in a position of privilege, i feel i have no choice but to do more and take on more. i won’t ask my RAs or TAs to do anything they are not paid for as that would be unethical — but the work still needs to be done, so I do it myself. i do it unpaid, in my ‘own’ time on weekends and at night. i suppress fits of spitting anger when i discover the way that colleagues readily exploit others —– like not paying tutors to deliver their lectures. i feel tired and angry most of the time but can’t complain because at least i own my job. not everyone is so lucky. but i can feel the hordes (younger, smarter, quicker, more compliant, hungrier than me) that are ready to take to my place (for less) if I say no or am too difficult. this isn’t a good situation for me or for them. but i won’t see them as enemies or competition. they are colleagues who don’t have my opportunities and i fear for their future.

Teaching experience is worth almost nothing in the academic job market (compared to research outputs). I now tell new PhD students to avoid casual teaching. There will be plenty of time to “get teaching experience” after you submit your PhD (and you’re trying to get your first aca job). Make full-time staff do the teaching and assessing that’s in their contracts. If full-time staff have too much teaching they should take it up with the union or the management of the department.